The Amateur Lord of the Rings (27.07.15 by Barry Stead) -

Comments

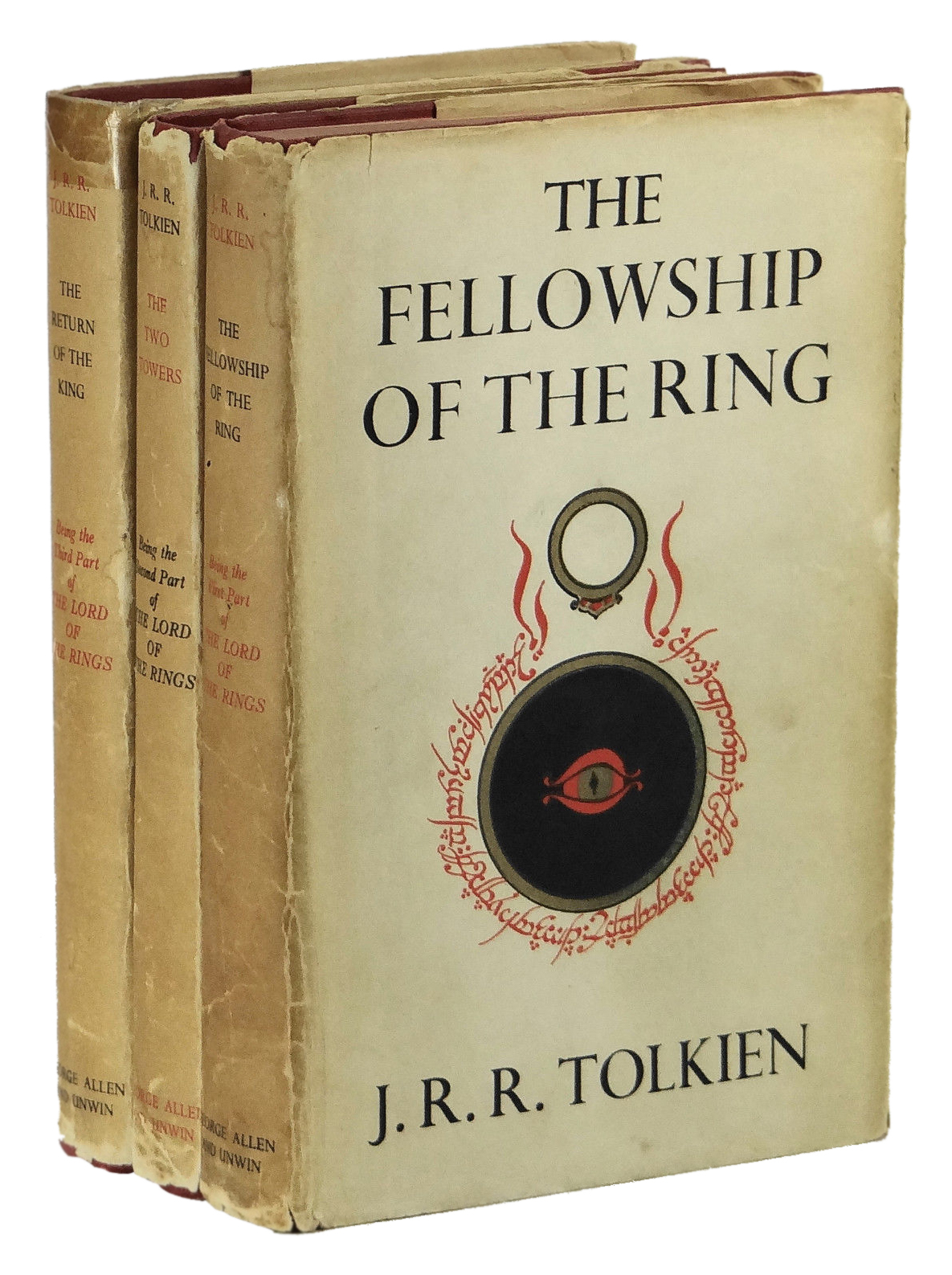

No other work of literature in the 20th century can claim such influence among so many, and indeed now on the frontier of discovery, an area of Pluto's moon Charon has been named—provisionally—Mordor.

One has to ask why, what are its peculiar qualities? Time and again it tops, or is a runner up with honours, in various best book/favourite book reader-voted contests. What is in it that it reaches out to so many. For it is a book not taught at school, nor is it short unlike To Kill A Mocking Bird (which is taught in schools), and which frequently achieves high honours in similar beauty pageants. One can list the wide scope of tolkien's imagination, his narrative strength, the many vistas (in some ways the book is a travelogue of wondrous lands), his strongly defined characters or the consistency of his nomenclature which has a subtle and strong contribution to the verisimilitude of the imaginary world. We can tick these off but we can tick these boxes with other authors going back to Jonathan Swift and now coming up to Game of Thrones, which probably has more in common with the Hundred Years War than The Lord of the Rings. There are people who say that they love the book; but there are those who say it has changed our lives. What is it about the book and its writer that pierces and reaches so many?

Despite being a professional philologist, academic and administrator, I think it was because Tolkien was an amateur writer; he was not writing for money, he was not hacking around in Grub St to pay the rent. Unlike the professional writers of his time, or those who worked in the modish literature business, like T S Eliot, Ezra Pound or Virginia Woolf, he could let the need to be seen and to be seen to be contemporary or relevant pass him by. So he could write what he liked and about what he wanted. And like a train spotter or manic gardener devoted to their fancies he just sat down and wrestled with the themes that dominated his mind; and I think we can say these were death and loss, and the passing of a more perfect time (or Age).

Because he had no pretentions to being a professional writer—but that is not to say he had no idea of his own considerable powers—he wrote like a sort of literary everyman and these themes that touched him and moulded the great scenes in the Lord of the Rings—themes that rise from the narrative—touch us because we wonder what we would do in such situations: could we be Frodo? Or Sam? How would we face life in the trenches, or the implacable walls of Mordor. And there is terror and fear in The Lord of The Rings and at times a sense of hopelessness in the Quest. Were these feelings held by a frightened young second lieutenant all through the Battle of the Somme?

It is significant that the first story he wrote after being whisked out of the Somme by fortune was a work of imaginative literature (as Christopher Tolkien would later put it); and so often have writers resorted to works of imagination to deal with inexpressible horror or danger faced in reality. This was the Fall of Gondolin, a Tolkienian re-working of the second book of the Aeneid (remember Tolkien was an accomplished classicist before hopping courses to study English), and for the next two decades he struggled with the work that was to become The Silmarillion, a meditation on death where mortality and immorality are juxtaposed. The Hobbit was a mere jeu d'esprit halfway up this mountain but in it, where Tolkien the amateur writer = Bilbo Baggins = us, meets and deals with the issues of death and battle, and courage and fear. In Beorn's house the warg and goblin are very truly and bloodily dead – this is just one example but it shows the reality of the emotions and ideas he is subliminally processing. The ending of The Hobbit is so different from the usual children's literature of the period, and especially the literature Tolkien grew up with – it is the ending written by a man who has seen the Western Front, the disenchantment of the 1920s and the General Strike of 1926. There are no tidy, happy endings.

He himself said in the preface to the second edition of The Lord of The Rings that its effect lies in the applicability of aspects of the story on an individual reader's situation (against the purposed domination of the author in an allegory which he said he detested). This is true but it is the topics, the hopes, the fears that Tolkien the amateur author (= us) chooses to write about as an ordinary middle class man, and no member of a vying fashionable literary elite, that gives his works their universality and power...and tremendous reach.

About Barry Stead

Barry Stead is a writer, and teacher of digital graphics living and working in London.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: