Beyond Birthdays: an exploration and analysis of Letter 214 (29.09.14 by Tedoras) -

Comments

The general query that elicited the response that we now call letter 214 centers, most intriguingly, on the notion of birthdays; specifically, the notion of who gives whom a present in hobbit culture. Birthday customs and traditions, we learn, are firmly entrenched tenants of all hobbit societies; this should come as no surprise, given the enduring importance of kinship to that folk. And Tolkien, thus, addresses birthdays from a social angle.

In this letter, Tolkien introduces us to the term ribadyan, the formal name for one celebrating his or her birthday. In Old English, he renders this name as byrding, derived from byrd meaning “birth.” The customs surrounding birthdays, he explains, had “become regulated by fairly strict etiquette” (Letters 290). It was custom, contrary to the belief of many, for the byrding to both give and receive presents on the big day.

The reception of gifts, Tolkien elaborates, is “the older custom” (Letters 291). The roots of this tradition lie in hobbits’ fidelity to kinship. The gift received, therefore, served more as a recognition, a ceremonial token of that hobbit’s “incorporation” in his specific house or clan (Letters 291). Tolkien explains that in older times, the first such gift of recognition one received was the formal announcement of his name after birth to his assembled family; however, over time, this gift manifested itself as a physical present. Yet, still none of our present notions of quantity are applicable; the byrding received but a ceremonial gift from the head of the family, and never anything from his parents save in case of adoption (a rather curious, undeveloped condition).

More importantly perhaps, though certainly more characteristic, is the giving of gifts. This is not limited to kinship, yet remains a sort of recognition of affection, gratitude, and continued goodwill. This tradition begins as early as the third birthday (around the time hobbits become “talkers and walker,” also known as “faunts”). These gifts are supposed to be productions of the byrding, and as the task of creation and innovation may be hard on a small hobbit, children begin simply with the offering of flowers to their parents (Letters 291). Tolkien describes this conveyance of a good produced or grown by oneself to another as a form of “thanksgiving.”

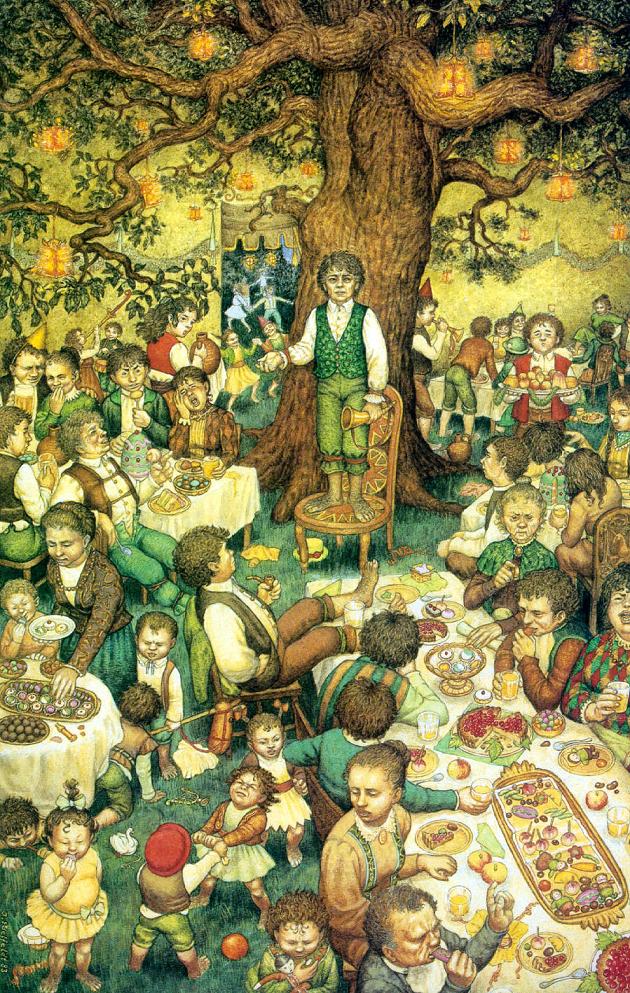

Yet, Tolkien says, “custom did not demand costly gifts,” nor the showing off and grand display thereof; hobbits preferred a more surreptitious approach to the giving of gifts, one rid of all pomp and tendency to induce ignominy at such expenditure (Letters 292). Most hobbits of average status in their families and of modest means would give simply as they could afford; thus, the Professor adds, Bilbo’s birthday party was considered “a riot of generosity even for a wealthy hobbit,” especially since any hobbit invited to a birthday party was customarily given a present (Letters 292). Even those dearest acquaintances that could not make it to the party for whatever reason were afforded that honor, as a gift would be sent along with their invitation. (I think it is fair, in the case of Bilbo’s farewell party, to assume that only, or at least, those members of the “gross”—the 144 special guests—all received presents. Imagine having to dole out nearly 150 gifts on your birthday!)

The scholar in Tolkien immediately recognized that any elaboration raised more questions than it answered; he was, however, determined to answer even those questions. So, he ventures to comment on some distal corollaries to the theme of birthdays. Thus, we learn that hobbits were, perhaps as we expected, “universally monogamous,” though that is a most unequivocal claim (Letters 293). While familiar patrilineal customs were the norm, most clans and households were not patriarchal monarchies; rather, Tolkien says, they were dyarchies, “in which master and mistress had equal status, if different functions” (Letters 293). Where the eldest male would normally serve as head of a family unit, in the event of the patriarch’s death, his wife would merely assume the post he had formerly occupied, and thus, he makes clear, no title would “descend to the son, or other heir, while she lived” (Letters 294).

The example Tolkien highlights surrounds the Baggins headship. Laura Baggins had served as head of the family until her late death at 104 years old; her son, Bungo, was thus only offered 10 years at the post, as he assumed it at the ripe age of 70 and died at 80; Bilbo, as we know, was left in some doubt after the death of his mother, Belladonna. Here, many a particular legal matter arises. Tolkien is quick to point out the confusion faced by these hobbits. For Otho (of the Sackville-Baggins line) was heir to the titular headship, though in this case, as in many, property did not transfer; thus Bilbo, much to the eternal chagrin of the Sackville-Bagginses, kept Bag End (Letters 294). However, the problem only grew in complexity; Otho died, then so, too, did Lotho and his wife, Lobelia; then Bilbo departed for the West and “it was still held impossible to presume death” (Letters 294). This mess led then-mayor Sam Gamgee to decree a law that allowed for the conferral of property to an heir in the event of one’s passing into the West and determined intent not to return; at which point, Tolkien notes, Ponto II most likely assumed the title of “head” (Letters 294).

All references to the text from: The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Humphrey Carpenter, ed. with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien. London: George Allen & Unwin; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Authors: Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin

Publication Date: October 15, 1981

Type: hardcover, 463 pages

ISBN-10: 0395315557

ISBN-13: 978-0395315552

About Ted Fruchtman

Ted is a scholar, bibliophile, and linguist who regularly publishes about Tolkien online. Be sure to look for his works on TolkienLibrary.com and at theonering.net, where he writes under the name Tedoras.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: