Darkness Tangible (28.09.14 by Alex Lewis and Ruth Lacon) -

Comments

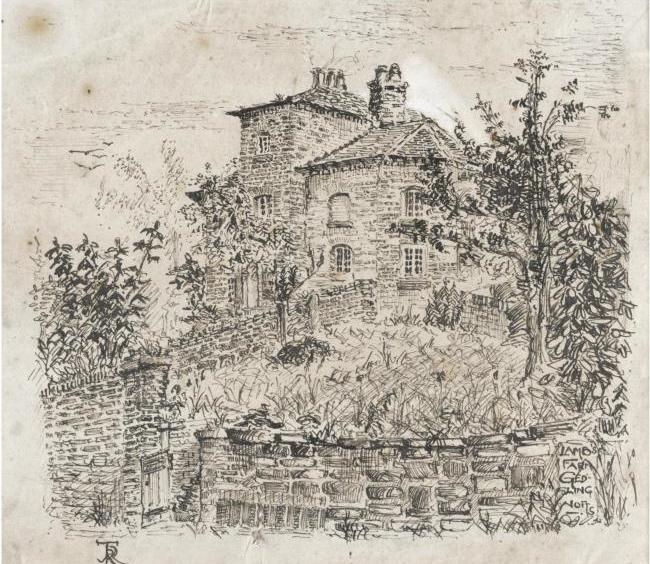

We know Tolkien painted with watercolours for most of his life – he did scenes of farmhouses (such as Gedling) and seaside (in Cornwall). One imagines that he must have been taught the basics of watercolour technique when he was at King Edwards school in Birmingham.

Part of that technique – as with all media – is the rule of light and shade which it imposes.

With a translucent, indeed virtually transparent medium such as watercolours, it is the white surface beneath that provides the light to the painting. A watercolourist always works from light to dark; they cannot go the other way. One of the hardest lessons for the watercolour beginner is to have to think like that, and not overdo the darkness.

Sponging out and other ‘lifting’ techniques never fully restore the pristine light of white paper. Darkness, in painting with such a medium, stains irrevocably. You cannot go backwards; light once splintered cannot be reunited.

The same is true of the other media which we know Tolkien worked in, such as inks and coloured pencil.

By the time when Tolkien was at school, oil-painters generally preferred to work the same way, from light to dark, though their medium does have the capacity to reverse that and overlay light. The most opaque media, gouache and tempera, which allow the artist to work from dark to light, are also the ones most rarely used. As far as we know, Tolkien never used either of these media for his paintings.

So whereas science would tell you that a shadow is the absence of light, and darkness is a lack rather that something in and of itself, in painting you have to ‘add’ shadow or dark by various techniques. Thick darkness is hard to achieve; it takes a lot of very material pigment to get it.

Darkness becomes a thing in and of itself. It has substance.

The painter’s darkness is an extension of the thinner aerial darknesses of Tolkien’s time. Smoggy dark fogs had a definite colour of their own, yellowish, reddish, dark grey – as well as affecting the daylight or moonlight that filtered through. They had a palpable presence as well, a burning in the back of the nose and throat, an oily smear on door handles or, in extremes, even on furniture indoors. Floating ‘smuts’ of soot like black snowflakes bedevilled housewives, fashionable ladies and small boys with immaculate collars.

Then there was the deeper darkness of the industrial revolution. Tolkien would certainly have known of the paintings of medieval Oxford by the likes of J.M.W. Turner in pre-industrial revolution times, with the colleges made of Cotswold stone, which is a honey coloured limestone. But the industrial revolution had turned all the spires and buildings black with soot and grime. Tolkien would have also been reminded of what the colleges used to look like, and what they ought to have looked like, when travelling to visit his brother Hilary in the Pershore area. Moving through the Cotswolds, and from Oxfordshire into Gloucestershire, he would have seen Cotswold stone cottages in villages far from the industrial atmospheres, and so untainted and still their original golden yellow splendour. Seeing that, he would have associated the Machine age with darkness tangible, and thus by extension, evil. In Tolkien’s time, the car and the internal combustion engine that drove it were inefficient and highly polluting machines – creating the choking fumes that added to the fouling effects of industry. It is ironic that some of the modern automobiles of today with their filters and catalytic converters in large city conurbations pump out air that is cleaner than that which they take in. But that was not the case in Tolkien’s time. Indeed, to find a comparable situation to what it might have been like walking down Cornmarket Street or the High Street in Oxford when they had vehicles running up and down their lengths all day long, one has to look to places such as Bangalore in India, where at rush hour the air literally catches your throat – the two stroke tuk-tuks and diesel trucks and busses pump out truly noxious fumes that would be banned in most modern western countries nowadays.

So, Tolkien’s view of darkness is one of activity not passivity – a something, a presence, not an absence.

This has perhaps an important consequence in Tolkien’s writings – most obviously in The Silmarillion where Ungoliant devours the Two Trees and spews out a darkness that removes sight and blocks the mind from functioning. Until that darkness clears, the Valar are unable to pursue her and Melkor, and by then it is too late and they have escaped across the Helcaraxë and into Middle-earth.

In the light of the last fruits of the Two Trees, the sun and the moon, the light has been tainted and is not the pure light of the Two Trees any longer. The only place where such light exists is in the three silmarils that were made by Fëanor, capturing and mingling the light of the Two Trees before they were poisoned and tainted.

In a similar way, when Frodo and Sam enter Shelob’s Lair, the darkness created by her webs seems to be a thing of substance. It is not mere absence of light and therefore sight; it is a physical obstruction.

One can perhaps expand that into the realm of whether evil is a thing in and of itself, Manichaeism versus the Platonic view of evil being an absence of good. The viewpoint can be seen to be a natural extension of the way a painter would observe and work upon a painting.

There may also be within this notion a starting point for the formation of the character of Gollum, early on in the conception.

Thinking as an artist – Tolkien’s paintings are what art critics would call ‘naive’. Now, let us propose that Tolkien painted a representation of Bilbo standing in a dark passage (perhaps when escaping from Goblin Town). He would have to paint his shadow – if we think to the way he portrays the trolls, it is likely that what he might paint on a cavern wall to represent Bilbo’s shadow would look like nothing less than a malevolent stalking creature. A kind of evil cousin to Peter Pan’s shadow. This would surely be the stuff of a child’s nightmares! If one of his children were unsettled by that notion on seeing such a painting, Tolkien would have to explain away the creature ‘dark as night’ that follows silently behind and always keeps to the shadows. It would by definition be ‘a Gollum’ – one of many such creatures – for all of us cast a shadow. All of us are followed by our shadow-forms.

Tolkien explores this idea of who has a shadow in one of his poems, Shadow-Bride, included in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (no.13 on p.52). A man who ‘dwelt alone’ and ‘sat as still as carven stone, and yet no shadow cast’ where a man who casts no shadow captures a woman to be his wife: ‘he woke, as had he sprung of stone / and broke the spell that bound him; / he clasped her fast, both flesh and bone / and wrapped her shadow round him.’ Once he has acquired this partner and her shadow the man is no longer condemned to a lone, stony exile. Instead they both live in an underworld ‘below where neither days / nor any nights there are.’ Once a year, though, when ‘caverns yawn’ they can emerge and ‘dance together then till dawn / and a single shadow make.’ The whole piece is atmospheric and ominous; the shadowless man’s need for a shadow turns him into a ‘malevolent fairy abductor’ preying on a woman, a character type otherwise singularly absent from Tolkien’s writing, though common enough in folklore and ballad.

This ‘independent shadow’-creature might be turned somewhat less malevolent by giving it a name and personality – by turning it into Gollum. This does seem to us to offer an amusing possibility; at that time (and indeed today, should you wish to seek one out) there were rag dolls made of dark material which we call ‘gollies’. Even the Robertsons jam jars had them on their labels as a kind of mascot. If one turns ‘a golly’ into a Latinate form, as a family of boys all learning the language at school and with a philologist for a father surely would, one ends up with Gollii, Gollae, and of course Gollum. Gollies - just like Gollum - have two round pale eyes and are ‘dark as night’. Had Tolkien suggested to a frightened youngster that the bogeyman evil shadow that followed them around was nothing more than a familiar and harmless ‘golly’ doll? We shall never know for sure, but it is a tempting thought.

Our slight descriptions of Tolkien’s technique as a painter do mention that, whilst he mainly worked in ‘light to dark’ media such as watercolour, inks and coloured pencil, where the underlying condition is the white paper and it is darkness that adds the most layers, he did also make some use of opaque white. In The Tolkien Family Album (HarperCollins 1992), amidst a description of the delightful art materials in her father’s study, Priscilla Tolkien ‘clearly recalls her father showing her how beautifully Chinese White could be used’ (pp.56-7). This was almost certainly ‘permanent white’ gouache of some description. Which would turn light into a solid and visible substance, not just an absence of darkness. Old-fashioned lead white and (to a slightly lesser extent) the modern titanium whites, allow for strokes of light over a dark surface which are as crisp, fine and telling as those of dark over a light surface. In The Book of Lost Tales Tolkien revelled in descriptions of light as a substance, especially as a liquid, and he never seems to have given up this idea, however ‘unscientific’ and awkward it became. Its reality and sensuous strength do compare well with the painter’s discovery that there is a way to work ‘light over dark’, and the creamy sensuous flow of the thicker opaque media on the brush and paper compared to the thinness, the near-absence, of watercolour or ink.

We hope this excursion into Tolkien’s talents as a watercolourist has illuminated some of the possibilities in terms of the background philosophy inherent within Arda and also some of the strange characters therein.

Authors: Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull

Publisher: HarperCollins

Publication Date: New Ed edition, 15 Jun 1998

Type: paperback, 208 pages

ISBN-10: 0261103601

ISBN-13: 978-0261103603

About the authors

Ruth Lewis is a Scot who started out as a zoologist and went on to become an artist and illustrator. A long-term member of The Tolkien Society, she has contributed articles, stories and artwork to their publications. Ruth paints under the name of Ruth Lacon and writes as Elizabeth Currie, to avoid confusing herself let alone anyone else. She has illustrated privately published books on Tolkien, including The Tale of Gondolin, and exhibits regularly in Wales.

Alex Lewis was born in Oxford, Britain, and grew up just round the corner from tolkien's houses in Northmoor Road. He too started out in the sciences as an industrial chemist, but prefers to describe himself as a novelist and symphonist. His music accompanied the 'Aratalindale' costume presentation which won four awards including Best in Show at this year's Worldcon in London. Alex is also the Tolkien expert for the travel company Alpenwild's 'In the Footsteps of Tolkien' tour of Switzerland.

Alex and Ruth have written three books on Tolkien and they are currently working on a Tolkien biography which will hopefully be published soon.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: