On Tolkien fundamentalism (23.04.14 by Simon J. Cook) -

Comments

Still, the April 1st dating may have deflected attention from the pressing question of Tolkien fundamentalism. Certainly, the resulting discussion largely bypassed this subject. In an attempt to face the issue squarely I offer now a textual sequel in which I rehash the same arguments under a different title.

Tolkien fundamentalism has its roots in an opposition to modernist interpretations of Middle-earth; such as, some might claim, the introduction of female Elves unmentioned in Tolkien’s texts.

The pejorative associations of the term ‘fundamentalism’ notwithstanding, Tolkien fundamentalism has a lot going for it: one way or another we must establish some red lines in the struggle against the commercially-driven abuse of Middle-earth. The present writer confesses to a moderate Tolkien fundamentalism.

But when pushed too far Tolkien fundamentalism embraces a fanatical literalism that is deeply at odds with the spirit of Tolkien’s work. This is because Tolkien was a ‘philological author’ and, as such, it is only right and proper to subject his texts to close philological scrutiny. Such scrutiny, or so I argue, is incompatible with the textual literalism of extreme Tolkien fundamentalism.

To give (again) my favorite example: the names of most of the dwarves in Thorin’s company, as well as that of Gandalf, are found in the Old Norse Poetic Edda. But (explains Shippey) ‘Gandalf’ does not fit in a catalogue of dwarves; this because the second part of his name means ‘elf’. Pondering this puzzle, Shippey suggests, led Tolkien to (1) suspect the ‘elf’ bit of the name to be a confused reference to magic, (2) connect the first part of the name – which means something like ‘staff’ – also with magic, and so (3) arrive at the idea of Gandalf as a (non-Elvish) wizard. Further meditation generates the conception of The Hobbit as a long-lost story explaining how the name of this wizard comes to be found in a list of dwarves.

The general lesson is this: Middle-earth is not a fantasy realm born simply from the imagination of one author. It is the distant past of our own world, or at least of its stories. As such, Tolkien’s stories are embedded in the fragments of much older stories.

But if Tolkien was forging the stories of the past then complaints that Peter Jackson or others have ‘abused’ Tolkien’s texts seem to beg a fairly large question. For surely Tolkien’s entire legendarium is the product of rather similar ‘creative engagement’ with older literary forms?

And this question gains even greater force when we recall Tolkien’s literary conceit that he was but the translator of very ancient texts. If we accept this conceit and pretend along with him that the stories relating to the war of the Ring have come down to us through the writings of long dead hobbit scribes, then we can hardly avoid acknowledging the right of the modern philologist to investigate these hobbit writings together with other old stories of the North.

But philological engagement – as we have seen in the case of Gandalf and the catalogue of dwarves – is no friend of textual literalism. It is the business of philology to point to possible errors of transmission and to source bias and to posit missing elements of a story.

Extreme Tolkien fundamentalism is thus fundamentally incompatible with the philological spirit of Tolkien’s writing.

Let me leave you with the suggestion that we might profitably approach this sensitive subject by way of the following question: is the discovery of Gandalf the wizard in the ‘Catalogue of Dwarves’ of the Völupsá any more (or less) justified than the discovery of Tauriel in the text of The Hobbit?

Author biography

Simon J. Cook is a professional editor and independent scholar. His other writings can be found via his website: https://yemachine.com.

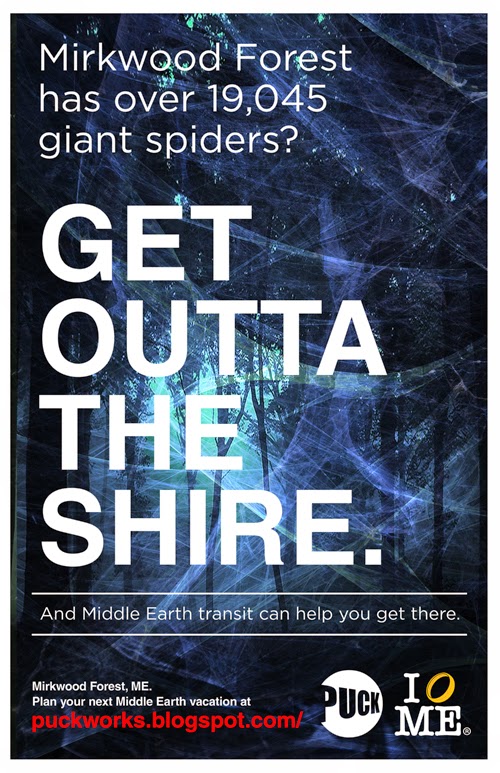

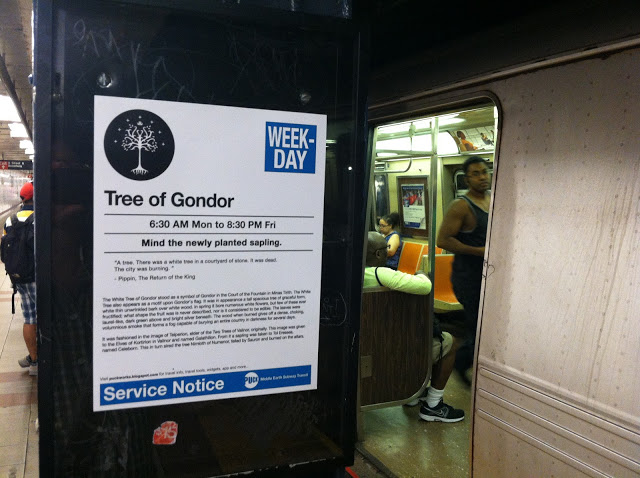

About the artist

Images (of a New Orc state of mind) used with kind permission of street artist known as PUCK.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: