On the Origin of Hobbits: J.R.R. tolkien's ideas of descent * (08.12.13 by Simon J. Cook) - Comments

Introduction

In this essay I continue my search for the origin of hobbits; a search that arose in the wake of an encounter with them – or creatures very similar – in a dusty volume published over a century ago.

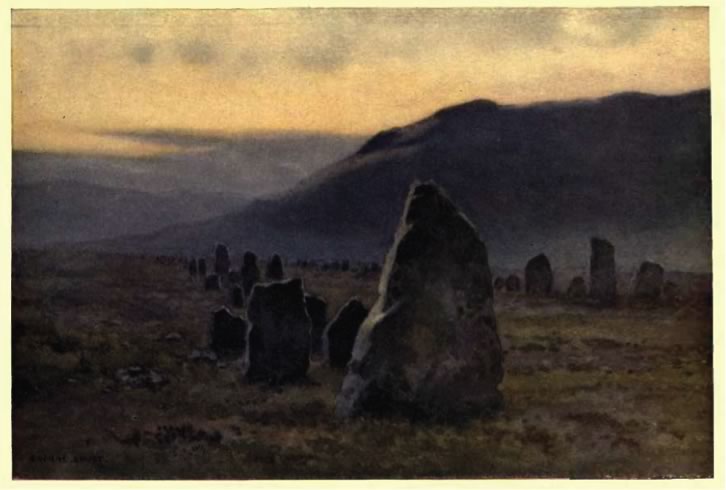

Here I came upon John Rhys, the first Oxford Professor of Celtic, describing some prehistoric dwellings that “appear from the outside like hillocks covered with grass”. To you and me these words of course conjure up an image of the home of Bilbo Baggins. Imagine then my surprise when Rhys went on to argue that the rooms of these prehistoric abodes were “so small that their inmates must have been of very short stature”.

Wondering whether I had stumbled upon a source of J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits, I set out to learn more about Rhys. An essay published on the ‘Tolkien Library’ website last summer (2013), Concerning Hobbits: Welsh Fairies in Oxford, tried to make sense of how Tolkien might have read and responded to Rhys’s ideas. This first essay contained some valuable insights. But at the time of writing I had not yet grasped the subtle if profound generational shift that separated these two Oxford philologists. Correctly intuiting some intellectual gap, I vaguely assumed that Tolkien’s account of hobbits poked fun at the scholarship of Rhys. Here I was hasty.

The present essay is an attempt to tidy things up. It sets out a sketch of the history of scholarship, from around 1860 through to the mid-twentieth century, into which the respective ideas of Rhys and Tolkien can be placed. (1) If the result leads by a different route to the idea that hobbits are indeed akin to Rhys’s British aborigines, it also points to errors in my previous interpretation.

In concrete terms, some of my earlier concluding suggestions (for example, that hobbits are implicated in an English colonization of Wales) now seem distinctly dubious.

Language and Race

In this main part of the essay I trace the changing relationship between ideas of race and language in British scholarship. We begin in Oxford around 1860, with the German Sanskrit scholar, Friedrich Max Müller, introducing the science of comparative philology to the rising generation.

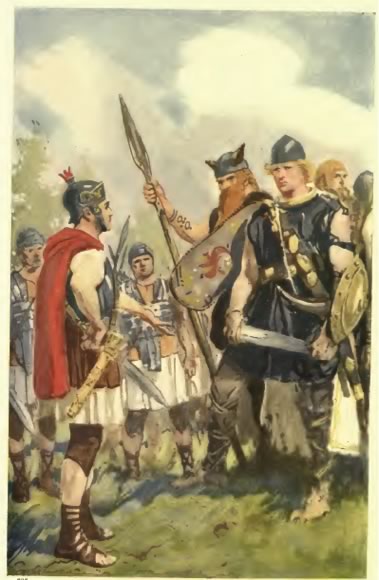

Max Müller was concerned with the genealogy of what he called the Aryan languages, which he conceived in terms of a branching tree-like model of descent. He conjured up an image of an original Aryan tribe, dwelling long ago somewhere in the East and speaking one tongue. From this primitive tribe had branched out numerous related races, heading both East and West, the bearers of different offshoots of the Indo-European family of languages. A single genealogy thus described both philological and ethnological relationships. In other words, Max Müller saw language and race as two sides of the same coin. (2)

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century Max Müller’s Oxford students staged an intellectual revolution. Their battle cry was “language is no guide to race”. At the heart of their new vision was a physiological conception of race, the markers of which were supposed to reside in the body, most importantly (at least when archaeologists were involved) the shape of the skull.

One implication of this intellectual revolution was the opening up of a potential space between linguistic and racial identities. Englishmen, for example, might have inherited their language and their cultural traditions from the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain, but the blood that flowed in their veins was derived from all invaders of the British Isles together with that of the earliest neolithic settlers. Indeed, to the extent that emphasis was placed upon the small numbers of the invaders, so to that extent the idea of racial mixture shaded into that of dilution, with the blood of the first settlers remaining the dominant strain even within the modern population. But in either case, racial identity was prioritized over linguistic identity by many late Victorian and Edwardian scholars. From their perspective, the blood that was shared by the inhabitants of Wales and England was deemed more significant than the different languages that might separate them. In this way, ideas of race undermined local English and Celtic nationalisms.

The scientific significance of racial evidence was thus undermined. One consequence was a shift back to an emphasis upon linguistic over racial identity, albeit still within the new model of warrior invasion and subsequent racial fusion. In the case of Tolkien, at least, a further consequence was the development of an additional, spiritual idea of identity, which combined aspects of both racial and linguistic identities and yet was deemed a mark of individuality. Both of these innovations are articulated in Tolkien’s 1955 lecture ‘English and Welsh’.

However, in the last part of his lecture Tolkien distinguishes the language that we first learned as a child from what he describes as an inherited “native language”, which we may never learn to speak, but which nevertheless governs our deepest linguistic yearnings and unexplored desires. The underlying idea appears to be that, alongside a cultural inheritance passed down from our speech ancestors, each one of us receives also a spiritual legacy from our biological ancestors. What this means is that, overall, each one of us receives three distinct inheritances: from our speech ancestors, a single cradle-language (and associated culture); and from our various biological ancestors, a mix of physiological features and several layers of inner disposition (of which one or other layer is perhaps dominant).

Hobbits

What has all of this got to do with hobbits? Let me try to answer by turning first of all to the population of modern England (and Wales). According to ‘English and Welsh’, the English count as English in the first instance because they have inherited a language (and hence cultural traditions) from the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain. And yet each individual has also an inner identity, which is in some way correlated with his or her biological descent. What is the dominant racial identity among English individuals? In his lecture Tolkien explains that, although the language of the first settlers has long disappeared from the British Isles, nevertheless the bearers of Celtic and Germanic forms of speech “have clearly never extirpated the peoples of other language that they found before them”. This suggests that Tolkien believed that a good part – perhaps the greater part – of the blood that flows in the veins of the modern English (and, indeed, also the Welsh) derives from the neolithic farmers who lived long ago, on the same soil, when there was less noise and more green. Many today who speak English or Welsh are thus possessed of an aboriginal spirit.

Hobbits, those most unlikely creatures imaginable, may appear when a modern reader peers into the mirror of Middle-earth. But care must be taken deciphering this reflection. The face in the mirror does not belong to one of Rhys’s aborigines, nor one of their modern day descendants; although it bears a family resemblance to both.

About the author

Simon J. Cook is an intellectual historian. His book, The Intellectual Foundations of Alfred Marshall’s Economic Science: ‘A Rounded Globe of Knowledge’ (Cambridge University Press, 2009) won the 2011 best monograph award of the European Society for the History of Economic Thought. Over the last few years he has become increasingly interested in the intellectual upheavals that followed the discovery of human prehistory in the nineteenth century. Most of his publications can be found at: yemachine.academia.edu/simoncook.

Footnotes

* With deep affection and yuletide cheer, I would like to dedicate this essay to Helen Bakker.

(1) The present essay sketches some of the ideas developed in my ‘On Welsh Marches: J.R.R. Tolkien, Identity and Hobbits’, which was written for an edited volume dealing with the history of ideas of race in the humanities. Readers seeking the source of citations and evidence for the various claims made here are referred to this longer essay which, while not yet published, can be found in a draft form on my academia.edu site.

(2) Of course, it was not actually believed that the language and (biological) race of any one individual necessarily coincide. Throughout history, it was pointed out, individuals and even entire peoples had been adopted into other nations, and had hence learned a new language. In this mid-Victorian vision it was language that was the dominant mark of identity; race was flexible.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: