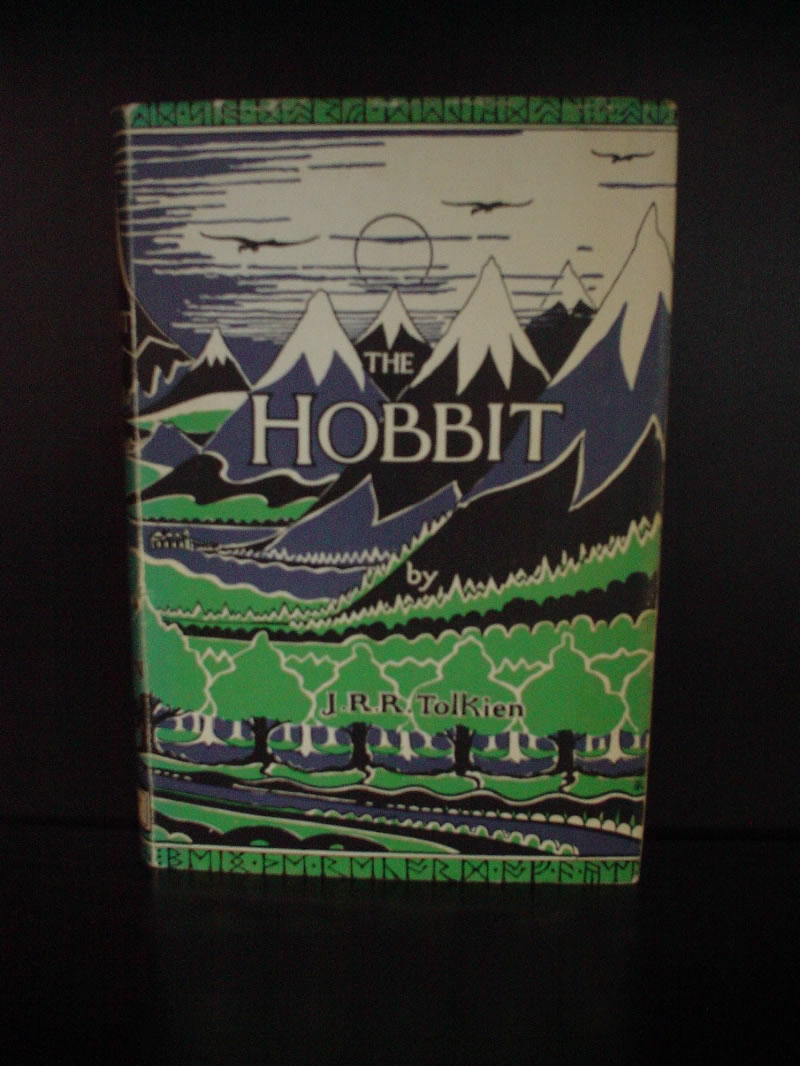

Books by J.R.R.Tolkien - The Hobbit

The hobbit-hole in question belongs to Bilbo Baggins, a very respected

hobbit. He is, like most of his kind, well off, well fed, and best pleased

when sitting by his own fire with a pipe, a glass of good beer, and a

meal to look forward to (which they take 6 times if they can).

Certainly this particular hobbit is the last person one would expect to

see set off on a hazardous journey; indeed, when the wizard Gandalf the

Grey stops by one morning, "looking for someone to share in an adventure,"

Baggins fervently wishes the wizard elsewhere.

No such luck however; soon 13 fortune-seeking dwarves have arrived on

the hobbit's doorstep in search for a master burglar, and before he can

even grab his hat, handkerchiefs or even an umbrella, Bilbo Baggins is

swept out his door and into a dangerous and long adventure.

The dwarves' goal is to return to their ancestral home in the Lonely Mountains

and reclaim a stolen fortune from the dragon Smaug. Along the way, they

and their reluctant companion meet giant spiders, hostile elves, ravening

wolves--and, most perilous of all, a subterranean creature named Gollum

from whom Bilbo wins a magical ring in a riddling contest.

It is from this life-or-death game in the dark that J.R.R. tolkien's masterwork, The Lord of the Rings, would eventually

spring. Though The Hobbit is lighter in tone than the trilogy that follows,

it has, like Bilbo Baggins himself, unexpected iron at its core. Don't

be fooled by its fairy-tale demeanor; this is very much a story for adults,

though older children will enjoy it, too. By the time Bilbo returns to

his comfortable hobbit-hole, he is a different person altogether, well

primed for the bigger adventures to come and so is the reader.

Editions:

George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. of London published the first edition

of The Hobbit in September 1937. It was illustrated with many black-and-white

drawings by Tolkien himself. The original printing numbered a mere 1,500

copies and sold out by December due to enthusiastic reviews.

Houghton Mifflin of Boston and New York prepared an American edition to

be released early in 1938 in which four of the illustrations would be

color plates. Allen & Unwin decided to incorporate the color illustrations

into their second printing, released at the end of 1937. Despite the book's

popularity, wartime conditions forced the London publisher to print small

runs of the remaining two printings of the first edition.

As remarked above, Tolkien substantially revised The Hobbit's text describing

Bilbo's dealings with Gollum in order to blend the story better into what The Lord of the Rings had become. This revision became the second edition, published in 1951

in both UK and American editions.

Slight corrections to the text have appeared in the third (1966), fourth

edition (1978) and fifth editions (1995).

New English-language editions of The Hobbit appear yearly, despite the

book's age. There are over fifty different editions published to date.

Each print comes from a different publisher or features distinctive cover

art, internal art, or substantial changes in format. The text of each

generally adheres to the Allen & Unwin edition extant at the time

it is published. It is though rather hard to keep track of editions and

impressions. There are many fourth editions books on the marked wich are

older then some 3th editions of other publishers. If

you want a more visual description of all hobbit editions you can find

it here.

The remarkable and enduring popularity of The Hobbit expresses itself

in the collectors' market. The first printing of the first English language

edition rarely sells for under $10,000 US dollars in any whole condition,

and clean copies in original dust jackets signed by the author are routinely

advertised for over $40,000. Online auction site eBay and Abebooks tends

to define the market value for those who collect The Hobbit. If you ever

thought of investing in books... a good copy of a 1st edition could still

be bought for about 2000$ in 1992... nowdays worth 5 times that much!

Also limited and deluxe editions are good investations, from the moment

they are sold out there value slowly grows.

The Hobbit has been translated into many languages. Some known languages,

with the first date of publishing, are:

• Albanian (2005)

• Arabic (2008)

• Armenian (1984)

• Asturian (2014)

• Basque (2008)

• Belarusian (2002)

• Bengali (2011)

• Breton (2001 / 2020)

• Bulgarian (1975)

• Catalan (1983)

• Chinese (Traditional characters) (2001)

• Chinese (Simplified) (2002 / 2013)

• Cornish (2014)

• Croatian (1994)

• Czech (1973 / 1979)

• Danish (1969 / 2012)

• Dutch (1960)

• Esperanto (2000 / 2015)

• Estonian (1977)

• Faroese (1990)

• Finnish (1973 / 1985)

• French (1969 / 2012)

• Galician (2000)

• Georgian (2002 / 2009)

• German (1957 / 1971 / 1998)

• Greek (1978)

• Hawaiian (2015)

• Hebrew (1976 / 1977 / 2012)

• Hungarian (1975 / 2006)

• Icelandic (1978 / 1997)

• Indonesian (1977)

• Irish (2012)

• Italian (1973 / 2004)

• Japanese (1965 / 2012)

• Korean (1979 / 1988 / 1989 / 1991 / 1999 / 2002 / 2021)

• Latin (2012)

• Latvian (1991)

• Lithuanian (1985)

• Luxembourgish (2002)

• Macedonian (2005)

• Marathi (2011)

• Moldavian (1987)

• Mongolian (2016)

• Norwegian (1972 / 1997 / 2008)

• Occitan (2018)

• Persian (2002 / 2004)

• Polish (1960 / 1985 / 1997 / 2002)

• Portuguese (1962 / 1985 / 1995)

• Romanian (1975)

• Russian (1976 / 1991 / 1995 / 2000 / 2001 / 2002 / 2003 / 2005 / 2014)

• Serbo-Croatian (1975)

• Slovak (1973 / 2002)

• Slovene (1986)

• Sorbian (2012)

• Spanish (1964 / 1982)

• Swedish (1947 / 1962 / 2007)

• Thai (2002)

• Turkish (1996 / 2007)

• Ukrainian (1985 / 2007 / 2021)

• Vietnamese (2003 / 2009 / 2010)

• West Frisian (2009)

• Yiddish (2012 / 2015)

If you know more dates about translations towards other languages , do

not hesitate to contact me:info@tolkienlibrary.com

Review:

Tolkien, a professor at Oxford University at the time he began writing

the book, said that it began from a single senseless sentence ("In

a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit") scrawled on an exam paper

he was grading. When he began, he did not intend to connect the story

with the much more profound mythology he was working on (see The Silmarillion).

However as Tolkien continued writing it, he decided that the events of

The Hobbit could belong to the same universe as The Silmarillion, and he introduced or mentioned characters and places

that figured prominently in tolkien's legendarium, specifically Elrond,

Gil-galad and Gondolin. Taken into consideration with the rest of tolkien's

work, The Hobbit serves as both an introduction to Middle-earth as well

as a narrative link between earlier and later events as told in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, respectively.

It has been suggested that The Hobbit can be read as a bildungsroman in

which Bilbo matures from an initially insular, superficial, and rather

useless person to one who is versatile, brave, self-sufficient, and relied-upon

by others when they are in need of assistance. However Tolkien himself

probably did not intend the book to be read in this way. In the foreword

to The Lord of the Rings he writes, "I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations,

and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its

presence." He claims that The Lord of the Rings is "neither allegorical nor topical".

It seems safe to assume that The Hobbit was written with the same caveats.

The judgement of Bilbo as "superficial" and "useless"

seems harsh since he was, according to Tolkien, rather typical of hobbits

in general.