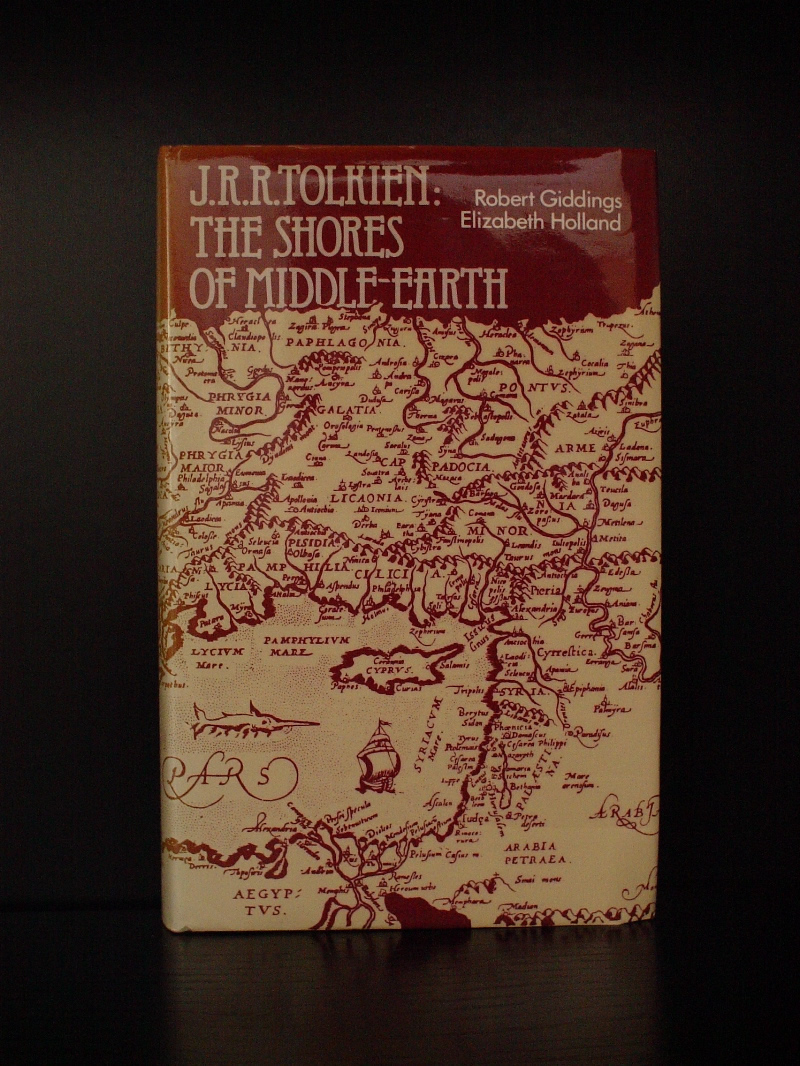

Books about J.R.R.Tolkien - J.R.R. TOLKIEN: The Shores of Middle-earth

tolkien's feat of imagination in The Lord of the Rings has been the cause of astonishment and admiration ever since the novel's first appearance in 1955. In The Shores of Middle-earth, published in 1981 and written by Robert Giddings and Elizabeth Holland, that feat is in a large part explained - and made, if anything, even more surprising. The Lord of the Rings is shown to be based on some of the most familiar texts of modern romance and fantasy - The Thirty-Nine Steps, King Solomon's Mines, Lorna Doone, Lost Horizon, The Wind in the Willows, and others - and on literary classics such as Shakespeare and Tennyson. These were all refashioned by Tolkien in terms of the seminal materials of European culture: the languages and myths of the Near and Middle East. Giddings and Holland, show that tolkien's sources lay where no one has suspected - and that the result is more ingenious and profound then even his greatest admirers have guessed.

Review:

Written in 1981 this book must have been an early try to show tolkien's sources. While the cover looks very inviting and the approach very academic, it seems this book is full of misinterpretations. Giddings and Holland make a valiant effort to place Middle-earth more geographically East, with the Shire (the

first setting for the book, from which Hobbits come) representing Asia Minor in Christ’s time, but ultimately their

argument fails. This reading certainly lends itself to an Orientalist interpretation of the text, but it is

fundamentally misguided.

It is an interesting book still, and a nice collectors item, but I would not recommend it to people who search more info on tolkien's sources, but to people who want to learn more about Orientalist Interpretations. There for I will here reproduce a brilliant article by Astrid Winegar, "Aspects of Orientalism in J.R.R. tolkien's The Lord of the Rings"

Was J.R.R. Tolkien an Orientalist? Though this specific question has apparently not been addressed before in scholarship, it is a valid query. Tolkien’s primary work, the epic heroic romance The Lord of the Rings, is replete with themes that directly pertain to discourses involving Orientalism and postcolonial concerns, such as racism, perception of the Other, and nationalism. The constant interaction between the various races of Middle-earth (some human; others not) invites the reader to analyze the role of Orientalism in The Lord of the Rings. In addition, the East/West binary construction necessitatesanexamination of the text in obviously Orientalist terms, if we define Orientalism as a way of looking at other people with preconceived assumptions and assigned notions of essential characteristics. While racism is implicit in Orientalism, not all racism is Orientalist. Orientalist texts traditionally reflect a Western way of examining the East; however, the Orientalist sensibility extends to any interaction between a so-called superior and a so-called inferior. We may further define Orientalist praxis as a way of looking at the Other in an abstract, racist manner. The Orientalist perceives the Other as static, eternal, exotic, dangerous, and inferior. Moreover, the Orientalist tends to encounter the Other non-empirically.

1

While Orientalism is identified as fundamentally racist, Tolkien writes about his somewhat racist

characters in both large ways as well as small ways that reflect a rejection of racist ideas. Tolkien’s

trilogy includes a definite dichotomy of East/West. In addition, discourse is always present, which

is not necessarily positive in nature at first, between Tolkien’s various invented races. These two

almost ubiquitous primary themes in The Lord of the Rings have a direct bearing on an

interpretation of the work as Orientalist in its perspective. Was Tolkien an Orientalist, however, or

did he only utilize Orientalist discursive practices to elaborate ideas that were decidedly anti-

Orientalist? Ultimately, Tolkien rejects Orientalism, though characters in his book sometimes

appear to be Orientalists themselves. What makes The Lord of the Rings unequivocally not a racist

text is the fact that Tolkien’s characters learn about others empirically. Many learn tolerance and

some become receptive to the transformative qualities of positive encounters with the Other.

Most authors can be easily misread or read superficially. Tolkien is no exception to this

problem, and this particular text occasionally has been labeled as atheistic, misogynistic, or too

childish, though very few children could actually understand the complex political and emotional

issues raised in the book.

2

Despite Tolkien’s protest in the introduction to the work that it not be read as allegory, sometimes the book is considered an obvious allegory for Adolf Hitler and World

War II, and The Lord of the Rings was also “forbidden in Russia for long years because of ‘the

Darkness coming from the East.’ [...] the censors regarded this as a clear reference to the

totalitarian system in the USSR” (Grushitskiy 233). A persistent criticism is that The Lord of the

Rings is a racist text. The work is rich in seemingly simple archetypal imagery: Good/Evil,

Light/Dark, Black/White, East/West, et cetera. Many times these words are capitalized to

emphasize their archetypal imagery, as opposed to simple adjectival usage. A cursory glance at

archetypal images such as these in the book, compounded by the recent film adaptations by Peter

Jackson, has led John Yatt to claim‘The Lord of the Rings’ is racist, [...] the races that Tolkien has put on the side of evil are

given a rag-bag of nonwhite characteristics that could have been copied straight from a

(British National Party) leaflet. Dark, slant-eyed, swarthy, broad-faced—it’s amazing he

didn’t go the whole hog and give them a natural sense of rhythm.

3

Yatt has neglected to delve more deeply into the mythological constructions and archetypal symbolisms that permeate the trilogy. Nevertheless, it is just this kind of blustery, ill-informed

commentary that might lead a newcomer to The Lord of the Rings milieu to have second thoughts

about entering Middle-earth, especially if a reader assumes that Tolkien’s writings only reflect the

prevailing postcolonial attitudes of the society in which he lived.

Granted, England in the early 20th Century was steeped in an Orientalist perception of the world

which is most evident in Great Britain’s relationship with India. However, Tolkien was deeply

offended by suggestions of racist attitudes, as is evident in his letters.

4

Born in South Africa in 1892, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien spent much of his adult life as a professor at Oxford University, England, from 1925 until his retirement in 1959. Tolkien was attracted to philology at an early age,

and learned many languages, from the classics, Greek and Latin, to the more obscure, less popular

Old Norse, Old English, and Old Icelandic. It is perhaps possible to trace any Orientalist ideas in

Tolkien’s Middle-earth mythology here because of his study of Indo-European languages, for this

would have led him to examine the work of Sir William Jones, which is seminal to the study of

comparative philologyaswell as to Orientalism. Two critics, Robert Giddings and Elizabeth Holland,

mention Sir William Jones, “the orientalist and jurist,” when making a connection between Tolkien’s

work and the Indo-European legacy (149). Considering that Edward Said calls Jones a “pioneer in

the field” of linguistics, Tolkien probably studied the work of Jones (8). Whether Tolkien adopted

Orientalist ideas from reading older philological works is hard to determine, but most likely, Tolkien

absorbed the philology while he rejected the racism.

Since he was a philologist by profession and at heart, Tolkien took great pains inventing various

languages to fit his created characters. Many have obvious similarities to languages that are known

to us. One group of Men, the Rohirrim, speaks a language identical to Old English. Of his Elvish

dialects, Quenya has elements of Finnish and Old Icelandic, and Sindarin has elements of Welsh.

Middle-earth is filled with languages as diverse as its many peoples, but there is a “Common

Speech” called, oddly enough, “Westron.”

5

Since Hobbits adopted this speech, it is safe to assume

that Westron is actually English, since “The Westron or Common Speech has been entirely

translated into English equivalents.”

6

It is convenient that almost all the characters are able to speak

Westron, and it becomes a sort of “universal translator” for the citizens of Middle-earth. While it

might seem a bit Orientalist to impose one language on all the peoples in the book, again, that

assumption would be a superficial misreading. The Common Speech is a convenience, but Tolkien

fully expects all his characters to revel in the use of their native languages, and spoken dialogue

and poetry are sometimes printed in individual languages in various sections of the book.

For Tolkien, language is obviously a desirable connection between people. The character of

Aragorn expresses the sadness of losing touch with others when he says of the Rohirrim, “their

speech is sundered from their northern kin.”

7

In Tolkien’s world, as in ours, language evolves;

people change. Sometimes they lose valuable qualities because of these changes. The only

language that Tolkien criticizes in The Lord of the Rings, however, is that of Sauron and Mordor,

the Black Speech.

8

This language is supposed to represent evil; thus, it is rarely spoken or written

in the book. It is supposed to sound harsh to most ears:

Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul,

ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul.

This speech was translated into Elvish script and carved onto the One Ring. Here it is in the

Common Speech:

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the Darkness bind them. (Fellowship 276)

On the actual Ring, this tyrannical sentiment was carved in lovely calligraphic Elvish letters that

have a decidedly Oriental look (Fellowship 59). Tolkien has chosen an Oriental style of script for

his Elvish lettering—this fact also supports an Orientalist reading of The Lord of the Rings, for

Tolkien’s Elves are described as rather exotic, eternal, and thus, susceptible to Orientalist

views. What removes Tolkien from the Orientalist standpoint is the fact that he has gifted the

Elves with a beautiful written language; nothing inferior is implied. Furthermore, the Black

Speech is not detested because it is from the East. It is loathsome because it represents

individuals who rule by oppression and tyranny, symbolized by the brutality of its language. In

Tolkien’s Middle-earth history, originally this evil power emerged from the Northern regions; so

again, we can see that Tolkien seems to use Orientalist themes, but the actual text reflects a

more balanced sensibility.

If we cannot establish Tolkien’s languages as unequivocally Orientalist, we might feel more

confident that Tolkien displays Orientalist tendencies in his description of the geography of

Middle-earth. Tolkien’s invented land bears a striking resemblance to the continents of Europe

and Asia. However, Tolkien was definitely an Englishman, and the Shire is an idealized

England. The primary evil power of the novel is positioned in the East; the heroic characters of

the novel are generally positioned in the West.

9

If we turn to Tolkien’s letters, we can obtain answers as to “where” Middle-earth really is. The Shire is England: “Hobbiton and Rivendell are taken (as intended) to be at about the latitude of Oxford.” In the same letter, Tolkien locates Middle-earth’s major city, Minas Tirith, “600 miles south, [...] about the latitude of Florence.”

10

King Aragorn is destined to return to this city.

11

The Eastern regions of Middle-earth are sketchy, and Tolkien does not seem overly concerned with their details. This implies that only the West is central to Tolkien’s vision, and

thus, also supports an Orientalist reading of The Lord of the Rings. Most directional names in

the trilogy are capitalized when they are used in an archetypal manner. Since this is an

adventure story involving a quest journey, however, most of the time directions are not

capitalized. Naming the direction of a particular region is problematic; as Gayatri Chakravorty

Spivak says, “[it] reveals the catachrestical nature of absolute directional naming of parts of the

globe. It can only exist as an absolute descriptive if Europe is presupposed as the centre” (211).

Tolkien’s themes were definitely centered on Europe. In a letter to W. H. Auden, he explains

why:

[...] a man of the North-west of the Old World will set his heart and the action of his tale

in an imaginary world of that air, and that situation: with the Shoreless Sea of his

innumerable ancestors to the West, and the endless lands (out of which enemies mostly

come) to the East. (Letters 212)

This does not mean Tolkien personally hated the East, or thought it inferior, but it does

demonstrate how a writer will effectively “write what he knows.” It is easy, however, to see how

Tolkien can be seen as an Orientalist, if we merely glance at some of his letters or at Middle-earth as it is physically depicted in the texts.

As we turn to the text of The Lord of the Rings, we read in the prologue about Hobbit history.

Hobbits are an invented race that stands for the rural English people. Their original home is

unknown, but long ago they all decided to move West. The returning king Aragorn has traveled

East, “even into the far countries of Rhûn and Harad where the stars are strange” (Fellowship

261). This might imply that the East is so different that even its constellations are foreign, but

Aragorn seems to be making more of a cultural statement, not only a scientific one, as he

wistfully describes his lonely life as a Northern Ranger. Tolkien’s Elves and Dwarves seek

refuge in the West as the threat of the East grows (Fellowship 52). As the main Hobbit

protagonist, Frodo, contemplates the evil Ring of Power, he felt that “Fear seemed to stretch out

a vast hand, like a dark cloud rising in the East and looming up to engulf him” (Fellowship 60).

From this, it is plain that the East represents at best an interesting element of exoticism and

at worst an almost palpable malevolence; hence, an Orientalist reading of Tolkien’s text makes

sense. However, Tolkien’s East is not inherently evil; it has become evil because Sauron, the

actual Lord of the Rings, has established his imperialist dominion over this region. Therefore,

Tolkien demonstrates he is not against the East per se, but he is against totalitarianism as it is

represented by the East in his Middle-earth setting. The Lord of the Rings is told from a singular

Hobbit perspective, not the perspective of a citizen of the East, and in that sense, we might

concur with the Orientalist, or racial reading. But Tolkien’s East could easily be West, or it could

be a tale of North and South; regardless of geographical locales, the story transcends these

boundaries and can be seen as a text of resistance to tyranny.

In addition to Orientalist readings of Tolkien’s invented geographies, many of the characters in

The Lord of the Rings express their concerns in Orientalist terms—all have some sort of

interaction with racism and dealings with the Other. Yet, while the characters easily display

elements of Orientalism, it is Tolkien who makes an effort to change their ideas.

While their stature is almost half that of most humans, Hobbits are the big heroes of The

Lord of the Rings. Hobbits can be divided into three distinctly different genetic types: one is of

fairer skin and hair, tall and slim; one stockier, with a larger bone structure; the final group was

smaller and “browner of skin” (Fellowship 12). This description alone refutes racist readings of

the text, because the color of a Hobbit’s skin is problematic. They are rustic in both positive and

negative senses of the word. Hobbits tend to be little Orientalists, for “they liked to have books filled with things that they already knew, set out fair and square with no contradictions”

(Fellowship 17). They are not imperialists, by any means, but their knowledge of other peoples

in Middle-earth is, for the most part, hypothetical. They fear strangers and prefer to think about

races such as the Elves in an abstract manner. They do not tend to travel, and those few who

get out of the Shire are looked upon suspiciously.

A few incidental quotes will demonstrate their

provincial qualities:

[...] It beats me why any Baggins of Hobbiton should go looking for a wife away there in

Buckland, where folks are so queer.

[...] And no wonder they’re queer,

[...] if they live on the wrong side of the Brandywine

River, and right agin the Old Forest. That’s a dark bad place, if half the tales be true.

[...] Not that the Brandybucks of Buckland live in the Old Forest; but they’re a queer

breed, seemingly. They fool about with boats on the big river—and that isn’t natural.

(Fellowship 30)

Not all Hobbits are so parochial, however.

Frodo Baggins [...] began to feel restless, and the old paths seemed too well-trodden. He looked at

maps, and wondered what lay beyond their edges: maps made in the Shire showed

mostly white spaces beyond its borders. He took to wandering further afield and more

often by himself; and Merry and his other friends watched him anxiously. Often he was

seen walking and talking with the strange wayfarers that began at this time to appear in

the Shire. (Fellowship 52)

Frodo has the advantage of being in a rather upper class, a bachelor, and nephew to Bilbo

Baggins, one of those suspect Hobbits who once traveled. This gives Frodo an outlook perhaps

more cosmopolitan than a typical Hobbit’s. On the quest, three other Hobbits accompany Frodo.

Two are younger, Merry and Pippin, both of whom are considered “Other” by some Hobbits of

the Shire, for their ancestral families are “different.” After various mind-opening adventures,

Merry and Pippin learn a great deal about other races. In the Appendices, we learn that they

serve as ambassadors to the king after the primary story has ended (Return 378). Though they

continued to live most of their lives in the Shire, each was laid to rest near King Aragorn in

Gondor, not in the Shire. They surpassed their Orientalist fears and prejudices and broadened

their horizons.

The other Hobbit accompanying Frodo on his quest is Samwise Gamgee, who is considered

by many to be the true hero of the trilogy. A modest gardener by trade, he is described as

Frodo’s servant in the beginning. Sam starts his wanderings with a narrow, Orientalist view of

any part of the world outside his own village, for “He had a natural mistrust of the inhabitants of

other parts of the Shire” (Fellowship 102). Since he mistrusted his close neighbors, one can

imagine his mistrust of other races living farther away. However, Sam is also fascinated by

Elves and stories about other places, but he is content to hear about strangers non-empirically

in a typically Orientalist manner.

Much to his dismay, Sam later witnesses a fierce battle between two groups of Men. One

group is allied to Gondor, or the West, “goodly men, pale-skinned, dark of hair, with grey eyes

and faces sad and proud” (Two Towers 267). Another group, called “Southrons,” is allied to

Sauron and the East, “swarthy men in red” (Two Towers 269). Sam is shocked at the sudden

battle, and more surprised when a Southron is killed by an arrow near him. The man lies “face

downward,” with an arrow below “a golden collar. His scarlet robes were tattered, his corslet of

overlapping brazen plates was rent and hewn, his black plaits of hair braided with gold were

drenched with blood. His brown hand still clutched the hilt of a broken sword” (Two Towers

269). This man is obviously not a fair-skinned English type, and here is the perfect opportunity

for Tolkien to demonize this enemy, especially since his actual face is not visible to the

provincial Sam (whose hands are also described as brown in other parts of the trilogy). Instead,

Tolkien treats the dead Man and the living Hobbit with compassion:

It was Sam’s first view of a battle of Men against Men, and he did not like it much. He

was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man’s name was

and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies or threats had

led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed

there in peace [...]. (Two Towers 269)

Sam is relieved not to see the face of the enemy not because of racism, or a desire to

dehumanize a foe. Sam sees beyond the skin color and the uniform; he makes an emotional

connection with this unknown Man. The enemy’s face is even more manifest to Sam, for he

intuits the life that existed before this senseless death and he mourns for this fallen Man.

Tolkien’s Elves are tall and elegant, and though they seem otherworldly, they are absolutely

bound to Middle-earth until their departure to the West. In addition, they are exotic, mysterious,

and immortal. As Frodo perceives the Elvish land of Lothlorien, we can sense the Orientalist

quality permeating the description of this “vanished world:”

[Lothlorien was] ancient as if [it] had endured for ever. He saw no colour but those he

knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had

at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful. [...]

Frodo felt that he was in a timeless land that did not fade or change or fall into

forgetfulness. (Fellowship 365-66)

This passage echoes Said’s discussion of Orientalist descriptions when he writes, “Something

patently foreign and distant acquires [...] a status more rather than less familiar” (58). Frodo is

experiencing this ultra-familiarity as he encounters this exotic, eternal land. Giddings and

Holland compare Lothlorien to the “idyllic Tibetan landscape [...] Shangri-La” of the novel Lost

Horizon by James Hilton (74). The innate quality of this Eastern Elvish Land is summed up by

Aragorn, when speaking of the land and the Lady who rules it: “There is in her and in this land

no evil, unless a man bring it hither himself” (Fellowship 373). Surely, this statement represents

how badly an Orientalist with a racist agenda can change the perception of an Eastern locale, in

fiction and in other works that appropriate the East as subject, especially when inaccurate, non-empirical rumors have fueled the reports.

Thus, it appears that the Elves represent more of the imaginative aspects of Orientalism, as

opposed to the fierce, but faceless, abstracted enemy from the East. Tolkien, however, is hard

to pin down here. The Elves perhaps represent the fancifully attractive elements of Orientalism,

the eternity, and exoticism. They are not inferior and not necessarily a people to be feared. If

anything, Tolkien appears to admire this race he invented, but only to a specific point. By

implying that the state of eternity ultimately, and undesirably, becomes a state of stagnation,

Tolkien is making a commentary against Orientalist perceptions. His concern for his Elves is

that a race which is perceived as changeless and eternal is doomed to oblivion. With the

advancement of the race of Men in The Lord of the Rings, the Elves become subject to a kind of

gentle genocide, whereby they sadly, but willingly, leave Middle-earth forever. Tolkien mourns

this loss of culture, but he also implies it is the Orientalist perception of any culture as static that

has forced this loss.

Another ancient race appears in The Lord of the Rings. Three wizards are named, though

only two are major characters. They are like Men, but also similar to Elves in that they seem

(from a Hobbit’s point of view) eternal, exotic, and perhaps, best known in an abstract manner.

Gandalf the Grey is the heroic wizard who displays few Orientalist qualities. Sometimes readers

might feel that certain characters (even sometimes a few characters) represent the voice of that

author. In this case, one could make an argument that Gandalf often sounds like the Tolkien we

might imagine. If so, then it makes sense for Gandalf not to represent Orientalist practices.

Gandalf is known for traveling extensively, and therefore, he has acquired empirical knowledge

of other people. However, he says, “to the East I go not” (Two Towers 279). Why not? For

Gandalf, avoiding the East is an excellent and practical way to avoid capture by the evil Sauron.

But if Gandalf sometimes represents Tolkien, this small phrase demonstrates only a lack of

interest in the East, not a perception that the East is inherently inferior or evil.

12

The other wizard Saruman, however, is another matter. Gandalf (or Tolkien) is extremely critical of this blatant Orientalist. Voluntarily confined to his black tower in Isengard, Saruman

the White has spent hundreds of years in deep study, and he has now decided to wield

imperialist power over Middle-earth. He feels every creature of Middle-earth is inferior to him.

He has acquired his knowledge from books, not from experience. Saruman perceives all the

races of Middle-earth as inferior and unchanging; therefore, he feels justified in ruling harshly

over them. It is Saruman who brings new technology to Middle-earth. With the character of

Saruman, Tolkien condemns the wholesale destruction of forests. Saruman also apparently

practices genetic manipulation of the main enemy race of The Lord of the Rings, the Orcs, in

order to breed a super army. This, of course, is our modern view of Tolkien’s ambiguous hinting

in the text. Tolkien would not have known about cloning technology, but his text is prescient

regarding the moral implications. Tolkien’s portrayal of Saruman as an Orientalist imperialist

academic is scathing, and Saruman is clearly one of the most evil characters in the book who

believes he is superior to all others.

Many instances of racism, imperialism, and the use of Black/White imagery foster superficial

readings of The Lord of the Rings as a racist text. Postcolonial discourse and Orientalism are

especially manifest in the interactions of Men in the novel. For example, the character of

Boromir is ostensibly a prince from Gondor, the land to which the future king, Aragorn, will

return. He is extremely proud, and his rhetoric is uncannily similar to some Orientalist rhetoric:

Mordor has allied itself with the Easterlings and the cruel Haradrim; [...] By our valour the

wild folk of the East are still restrained, and the terror of Morgul

kept at bay; and thus alone are peace and freedom maintained in the lands behind us,

bulwark of the West. (Fellowship 258)

Boromir seems to feel privileged to carry on with the White Man’s Burden, or noblesse oblige.

Not necessarily an imperialist, Boromir feels it is his duty to prevent the Eastern hordes from

invading the West. He is not wrong in this case, for Sauron is planning to send his troops West;

we must remember, however, that the Easterlings and the Haradrim are not portrayed as

inherently evil, as we saw in the episode between Sam and the fallen warrior. They are

perceived as the enemy by the Men of the West, but the Easterlings and the Haradrim are

completely under the will of a tyrannical power, Sauron.

A group of Men called the Rohirrim, or the Riders of Rohan, also exhibit Orientalist

tendencies toward their neighbors, the Drúedain, or Woodwoses. The Rohirrim regard the

Drúedain as inferior beings, best known in an abstract, non-empirical manner. The interaction

here fits an Orientalist approach to personal interaction with other races; to reiterate Orientalist

dogma proposed by Said, the Other is by necessity perceived as static and eternal, and is to be

feared.

13

This interaction comprises a small episode in The Lord of the Rings, but it is enough to

draw the attention of an anthropologist, Virginia Luling, who writes,

[...] they are very much the stereotype of the “savage.” Indeed their appellation“woodwoses” derives

from the sort of folkloric traditions from which that stereotype partly

derives; for Europeans when they crossed the oceans saw what their traditions

predisposed them to see, the embodiments of their own fantasies of “wild men”. They

are gnarled and strange in appearance, almost naked, communicate by beating drums,

are “woodcrafty beyond compare: [...] and hunt with poisoned arrows. One may add that

they are constantly hunted and persecuted by other sorts of men, [...]. The only thing

they are not is black, which would be incongruous in supposed ancient inhabitants at

this latitude. (55)

Here, apparently, we have patent Orientalist/racist tendencies in the novel. If we were to support

an imperialist outcome to this encounter, the Drúedain would need to be subjugated and their

conversation would seem unintelligible. Again, however, Tolkien rejects the typical Orientalist

approach.

The Rohirrim need the Drúedain’s guidance through a particularly tricky area. First, the

Rohirrim are surprised that the Drúedain’s leader, Ghân-buri-Ghân, speaks the Common

Speech, “though in a halting fashion, and uncouth words were mingled with it” (Return 106).

Ghân starts to explain his expertise, and one Rider asks, “How do you know that?” Instead of

reducing this “savage” to idiocy or fawning behavior, as an Orientalist writer might have done,

Tolkien characterizes his supposedly inferior savage as rebuking the Rider: “The old man’s flat

face and dark eyes showed nothing, but his voice was sullen with displeasure. ‘Wild Men are

wild, free, but not children’” (Return 106). The Rider is worried and impatient, but Ghân again

rebukes him: “Let Ghân-buri-Ghân finish! [...] More than one road he knows. He will lead you by

road where no pits are, not [Orcs] walk, only Wild Men and beasts. [...] Road is forgotten, but

not by Wild Men” (Return 106). They make an agreement, and the king of the Rohirrim says, “If

you are faithful, [...] then we will give you rich reward, and you shall have the friendship of the

Mark for ever” (Return 107). Being a practical, intelligent sort of man, Ghân seizes the

opportunity to protect his people from the persecution they have suffered:

Dead men are not friends to living men, and give them no gifts, [...] But if you live after

the Darkness, then leave Wild Men alone in the woods and do not hunt them like beasts

any more. Ghân-buri-Ghân will not lead you into trap. He will go himself with father of

horse-men, and if he leads you wrong, you will kill him. (Return 107)

Lest the reader forget this episode of racial interaction and education, King Aragorn and his

entourage pass by this area later. He proclaims: “The Forest of Drúadan he gives to Ghân-buri-

Ghân and to his folk, to be their own for ever; and hereafter let no man enter it without their

leave!” (Return 254). These “savage” people are given autonomy; healing has begun.

As stated earlier, The Lord of the Rings is open to many interpretations, and various right-

wing extremist groups have apparently adopted the text as crucial reading:

In 1977, Italian fascists ran a Hobbit Camp for their young supporters. The neo-Nazi

British National Party has declared “Lord of the Rings” essential reading. Charles John

Juba, national director of Aryan nations, says his organization welcomes the latest “Ring” movie because it is “entertaining to the average Aryan citizen.”

14

We can see how these groups might appropriate some of these Orientalist, racist, imperialist

themes, for superficially, the text appears to support these themes. This interpretation is

completely contingent on the Light/Dark binary. As Keith Fraser writes, “Tolkien was writing an

Anglo-Saxon mythology, and therefore it is hardly surprising if the ‘good guys’ in his imaginary

age are Anglo-Saxon in appearance and their enemies dark-skinned invaders from eastern or

southern lands”

15

Tolkien’s use of Light/Dark imagery is not so simple, however. Various individuals radiate with light, but “[Tolkien] also complicates [this imagery] deliberately—

Aragorn’s standard is mostly black; Saruman’s is white, [...]” (Chism 90). This is a tricky issue,

but it goes deeper than skin color. We cannot only base our knowledge on particular colors as

specific signifiers as Homi Bhabha does when he claims that “in children’s fictions, [...] white

heroes and black demons are proffered as points of ideological and psychical identification”

(46). This statement takes an exceptionally narrow view of a world that can only be seen as

black or white. Batman and Zorro are heroes though they are dressed completely in black—

their skin color becomes irrelevant. Certain archetypal images move us as human beings, and I

do not believe that seeing Orcs, for example, with pink hair and light green suits of armor would

really convey to any viewer or reader the appropriate sense of terror Tolkien was seeking in his

descriptions (except as a severe fashion faux pas...).

One particular chapter in The Lord of the Rings lends itself to further erroneous fascist

interpretations. When the Hobbits return home, they discover that Saruman has set up a cruel

dictatorship in the Shire. In no way does Tolkien claim this is a good situation, except in the

sense that the Hobbits are forced to face reality, confront the hostile invaders, and defend their

homeland. This incident forces the Hobbits to grow up a bit more, and it teaches them not to

take their secluded Shire for granted. This chapter, entitled “The Scouring of the Shire,”

sometimes strikes readers as somewhat incongruous to the text as a whole. However, it is a

necessary outcome and it facilitates Tolkien’s idea that maintaining a peaceful, provincial

lifestyle is worthwhile, but it requires work, not complacence. The Shire has opened both

physical and psychological boundaries because of the traveling Hobbits. A dictatorship must not

exist in the Shire. Tolkien writes that previously

The Shire [...] had hardly any ‘government’. Families for the most part managed their

own affairs. Growing food and eating it occupied most of their time. In other matters they

were, as a rule, generous and not greedy, but contented and moderate, so that estates,

farms, workshops, and small trades tended to remain unchanged for generations.

(Fellowship 18)

If anything, the Shire sounds like a rather idealistic and idyllic commune, which would partly

explain the appeal of the trilogy to readers, especially in the sixties. It is mystifying to hear how

particular right-wing groups could consider running Hobbit Camps, for the Shire/hobbit

philosophy is diametrically opposed to any type of totalitarian government, as demonstrated in

the quote above.

We can see that Tolkien often uses Orientalist/racist discourses to describe the geography

of Middle-earth and the interactions of its various races. However, he then criticizes these

notions and rejects them, supporting the argument that The Lord of the Rings cannot be seen

fundamentally as a racist text. In this way, The Lord of the Rings “ [...] does not celebrate

racism; rather it celebrates a delight in the cultural exchange made possible by the kinds of

mixed unions and alliances [Tolkien] celebrated in his narratives” (Straubhaar 116). At its core,

the trilogy is about healing and understanding the relationships between widely disparate

peoples. The potentially Orientalist themes are handled in a manner that encourages us to

embrace Otherness, not distance ourselves from it. His characters sometimes relate to other

characters in stereotypical ways, and sometimes the characters themselves are stereotypical.

These same characters sometimes voice their opinions in racist terms, but ultimately Tolkien

concludes his vast epic with positive qualities that strive to produce acceptance. Being a

postcolonial man of the 20th century, Tolkien addresses certain issues from a Western

viewpoint—but not a racist or Orientalist viewpoint. The Lord of the Rings is tinged with

sadness, but also happy moments. By the end of the novel, a deep friendship develops between

former rivals from different races (Elves and Dwarves), trade and work agreements between

races help rebuild Middle-earth (Elves, Dwarves, and Men), joyful interracial marriages take

place (such as that between the Man Aragorn and the Elf Arwen), and a more cosmopolitan

outlook emerges for Middle-earth’s citizens. It is hard to imagine these happy events taking

place while retaining an Orientalist perspective on the world.

Footnotes

1 The concepts of Orientalism are eloquently discussed at length in Orientalism by Edward Said.

2

The most vicious attack against the text appears in an article by critic Edmund Wilson, “Oo, Those Awful Orcs.”

This article is so misinformed, it is doubtful Wilson ever actually read the text. Other charges leveled against Tolkien

were addressed by him in one of his letters to his publisher, Houghton Mifflin Co.: “The only criticism that annoyed me

was one that [The Lord of the Rings] ‘contained no religion’ (and ‘no Women’, but that does not matter, and is not true

anyway). This statement, of course, has angered feminists, but has no bearing on this paper.

3 John Yatt, “Wraiths and Race,” Guardian Unlimited 2 Dec. 2002: <https://film.guardian.co.uk/lordoftherings/news>.

4

Specifically, letters 29, 30, 61, 81, and 294.

5

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring 13, hereafter abbreviated as Fellowship

6

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King 391, hereafter abbreviated as Return.

7 J. R. R. Tolkien, The Two Towers 112, hereafter abbreviated as Two Towers.

8

Mordor is the East—note the similarity to the word “murder.”

9

Giddings and Holland make a valiant effort to place Middle-earth more geographically East, with the Shire (the

first setting for the book, from which Hobbits come) representing Asia Minor in Christ’s time, but ultimately their

argument fails (250 ff.). This reading certainly lends itself to an Orientalist interpretation of the text, but it is

fundamentally misguided.

10

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien 376, hereafter abbreviated as Letters.

11

One could read this city as a metaphor for Rome, since Tolkien was a devout Catholic, but that hypothesis

could form the basis of another paper.

12 Tolkien himself never did travel to the East; Venice, Italy was about as far east as he ever

journeyed.

13

Dogmas are paraphrased from Edward Said, Orientalism 300-01.

14 Leanne Potts, “The Works of J. R. R. Tolkien: Rooted in Racism?,” Albuquerque Journal 26 Jan. 2003.

15

Potts E6.

Works Cited

- Bhabha, Homi. “The Other Question.” Mongia, Contemporary 37-54.

- Chism, Christine. “Middle-earth, the Middle Ages, and the Aryan Nation: Myth and History in World War II.” Tolkien the Medievalist. Ed. Jane Chance. London: Routledge, 2003. 63-92.

- Giddings, Robert and Elizabeth Holland. J. R. R. Tolkien: The Shores of Middle-earth. London: Junction Books, 1981.

- Grushetskiy, Vladimir. “How Russians See Tolkien.” Reynolds and GoodKnight, Proceedings 221-25.

- Luling, Virginia. “An Anthropologist in Middle-earth.” Reynolds and GoodKnight, Proceedings 53-57.

- Mongia, Padmini, ed. Contemporary Postcolonial Theory: A Reader. London: Arnold, 1996. Potts, Leanne. “The Works of J. R. R. Tolkien: Rooted in Racism?” Albuquerque Journal 26 Jan. 2003: E6-8.

- Reynolds, Patricia and Glen H. GoodKnight, eds. Proceedings of the J. R. R. Tolkien Centenary Conference. Altadena, CA: Mythopoeic Press, 1995.

- Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Poststructuralism, Marginality, Postcoloniality and Value.” Mongia, Contemporary 198-222.

- Straubhaar, Sandra ballif. “Myth, Late Roman History, and Multiculturalism in Tolkien’s Middle- earth.” Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. Ed. Jane Chance. Lexington, KY: UP Kentucky, 2004. 101-17.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. The Fellowship of the Ring, Being the first part of The Lord of the Rings. 2d ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

- ---. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Eds. Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

- ---. The Return of the King, Being the third part of The Lord of the Rings. 2d ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

- ---. The Two Towers, Being the second part of The Lord of the Rings. 2d ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

- Wilson, Edmund. “Oo, Those Awful Orcs.” Nation 14 Apr. 1956: 312-13.

- Yatt, John. “Wraiths and Race.” Guardian Unlimited 2 Dec. 2002: <https://film.guardian.co.uk/lordoftherings/news>.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: